In the annals of warfare, there has been nothing like DU, as it is often shorthanded. In both Iraq wars, and in Afghanistan, the U.S. military used depleted uranium to inflict enormous harm on the enemy while incurring almost none itself. During the first Gulf War, in 1991, "tank-killing" DU rounds brought Saddam Hussein's Republican Guard to its knees in only four days. Military experts estimate that at least 10,000 Iraqis were killed, compared with 147 Americans. In the corridors of the Pentagon, DU munitions quickly earned the nickname "silver bullet", and the Defense Department turned its attention to creating even faster, more powerful weapons systems fueled by depleted uranium.

"We want to be able to strike the target from farther away than we can be hit back, and we want the target to be destroyed when we shoot at it," Col. James Naughton told reporters at a Pentagon briefing last March. "We don't want to see rounds bouncing off. We don't want to fight even. We want to be ahead. And DU gives us that advantage."

In the annals of warfare, there has been nothing like DU, as it is often shorthanded. In both Iraq wars, and in Afghanistan, the U.S. military used depleted uranium to inflict enormous harm on the enemy while incurring almost none itself. During the first Gulf War, in 1991, "tank-killing" DU rounds brought Saddam Hussein's Republican Guard to its knees in only four days. Military experts estimate that at least 10,000 Iraqis were killed, compared with 147 Americans. In the corridors of the Pentagon, DU munitions quickly earned the nickname "silver bullet", and the Defense Department turned its attention to creating even faster, more powerful weapons systems fueled by depleted uranium.

"We want to be able to strike the target from farther away than we can be hit back, and we want the target to be destroyed when we shoot at it," Col. James Naughton told reporters at a Pentagon briefing last March. "We don't want to see rounds bouncing off. We don't want to fight even. We want to be ahead. And DU gives us that advantage."Five days after the briefing, U.S. forces launched the second war on Iraq. This time around, however, DU projectiles were exploded not only in uninhabited deserts but in urban centers such as Baghdad -- a city the size of Detroit. Stabilized in steel casings called "sabots", the shells were fired from airships, gunships, Abrams tanks and Bradley troop carriers, striking targets 1.5 miles away in a fraction of a second. The weapons contained traces of plutonium and americium, which are far more radioactive than depleted uranium.

The Pentagon insists that the weapons pose no threat to U.S. soldiers or to non-combatants. "DU is not any more dangerous than dirt," declares Naughton, who recently retired after years as director of Army munitions. But a broad consortium of scientists, environmentalists, and human-rights activists -- as well as thousands of U.S. soldiers who served in the Gulf in 1991 -- cite mounting evidence that depleted uranium will cause death and suffering among civilians and soldiers alike long after the war's end. DU projectiles spew clouds of microscopic dust particles into the atmosphere when they collide with their targets. These particles, lofted far from the battlefield on the wind, will emit low-level radiation for 4.5 billion years -- the age of the solar system itself. Some doctors fear that long-term exposure to such radiation could eventually prove as deadly as a blast from a nuclear bomb -- causing lung and bone cancer, leukemia, and lymphoma (a cancer of the immune system known in medical circles as the "white death").

"This is a war crime beyond comprehension," says Helen Caldicott, a pediatrician who has campaigned against nuclear weapons for years. "This is creating radioactive battlefields for the end of time."

Others are more measured but equally concerned. "There are medical nuances I don't fully grasp," says Chris Hellman, a senior analyst at the Center for Arms Control and Non-proliferation, in Washington, D.C.. "But if you're going to be fighting wars for the goal of winning hearts and minds and bringing democracy and the altruistic things we associate with the campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq, the last thing you want to be doing is poisoning the people you're trying to help."

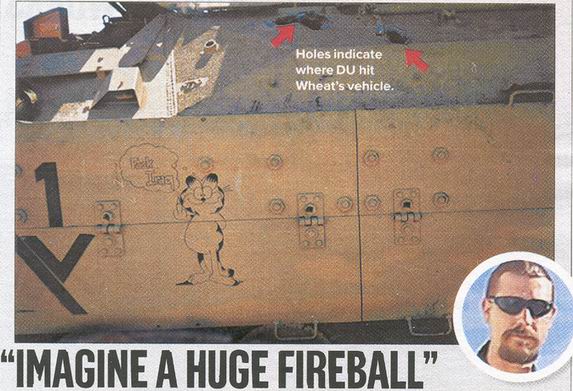

The percussion of the first shell pulverized a glass rosary inside the vehicle and knocked the crew unconscious. Jerry Wheat remembers popping the hatch, climbing out and pulling off his burning Kevlar vest. "My whole body was pretty much smoking." That's when the second round struck. "I could feel myself getting hit with shrapnel in the back of the head and back."

Wheat, a divorced father of two who works for the post office in Las Lunas, New Mexico, was twenty-three when he found himself halfway around the world in the Iraqi desert at the center of a fierce tank battle in 1991. A sandstorm was raging. He was driving a four-man Bradley fighting vehicle, on which one of his crew-mates had painted Garfield the cat saying, "Fuck Iraq." In photos of the vehicle, two jagged holes are visible at the top. That's where the Bradley was struck by "friendly fire" from an Abrams tank as Wheat steered toward the center of the battle and rescued members of another American tank crew.

A day later, Army medics removed pieces of shrapnel from Wheat's body as he lay on the back of a truck. Curiously, the wounds hardly bled, though second- and third-degree burns marked the entry points. "They were worried about a chest wound, but the shrapnel was so hot when it went in, it sort of cauterized, and I wasn't bleeding that bad." His sergeant major stopped by to tell him he had been hit by an Iraqi tank. "When we asked if we were hit by friendly fire, they said no, so I ate, slept, and lived off my vehicle for the next four days."

Wheat continued to drive the Bradley, though he noted a "dusty residue" coated it inside and out. "It was pretty nasty. Imagine a huge fireball going off inside your car - that's pretty much what the inside of my vehicle was like." He and his buddies also smoked eight cartons of cigarettes that had been stashed in the Bradley when it was hit. "You had these little pieces of metal falling out, and you would hold your fingers over the holes as you smoked them. They were all coated with DU. No one had ever even mentioned DU except to say that we were firing it. We were told not to worry. They said, 'It won't hurt you. It's depleted.' It was on your hands, your food. We didn't even think about it. We were just happy to be alive."

MILITARY SCIENTISTS BECAME intrigued by depleted uranium in the 1940s, at the very advent of the nuclear age. But it wasn't until the 1960s that American weapons designers began inventing ways to use DU in battle. Depleted uranium is what remains after "enriched" uranium, a crucial component in nuclear bombs and reactors, is processed from uranium ore. Although its radioactive properties have diminished by forty percent, it's hardly safe. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has strict rules pertaining to the handling and transporting of DU in this country -- rules that don't apply to the military during battle.

MILITARY SCIENTISTS BECAME intrigued by depleted uranium in the 1940s, at the very advent of the nuclear age. But it wasn't until the 1960s that American weapons designers began inventing ways to use DU in battle. Depleted uranium is what remains after "enriched" uranium, a crucial component in nuclear bombs and reactors, is processed from uranium ore. Although its radioactive properties have diminished by forty percent, it's hardly safe. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has strict rules pertaining to the handling and transporting of DU in this country -- rules that don't apply to the military during battle.Depleted uranium has long been used as ballast in military and commercial planes, but the introduction of DU onto the battlefield began modestly, without fanfare. According to a Pentagon official, U.S. troops carried DU "penetrators" into both Grenada and Panama. "It wouldn't have been very much, because there wasn't much to shoot at," says Naughton. "The first large-scale use was Desert Storm."

By its own estimates, the military exploded as many as 320 tons of DU in sabot-encased projectiles in the deserts of Iraq and Kuwait. Gunners shot DU rounds from the cannons of Abrams tanks or from airships such as the A-10 "Warthog". Depleted uranium is the heaviest of metals, which results in its superior penetrating abilities; it is also highly pyrophoric, bursting into flames at temperatures of 170 degrees Celsius. To imagine the carnage, one need only recall Iraq's infamous "Highway of Death", a desert road between Basra and Kuwait's border that remains strewn with radioactive trucks, cars, and tanks. U.S. soldiers found bodies inside those vehicles that were burned in such astonishing ways that they dubbed the remains "crispy critters".

Iraqi civilians were also exposed to low-level radiation from DU -- and preliminary evidence indicates that the consequences have been devastating. Iraqi doctors, many of them specialists trained at eminent Western institutions, such as Sloan-Kettering in New York or Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, report twelve-fold increases in Iraqi cancer rates since the first Gulf War, as well as sharp rises in birth defects in southern Iraq, where much 0f the fighting took place. According to Iraqi doctors, some infants there emerged from the womb with one eye, or no brain, or without limbs. They add that in the dozen years since the conflict, rates of childhood cancer linked to radiation exposure -- especially leukemia and lymphoma -- have jumped four-fold.

As for U.S. troops, the Pentagon says that only 900 of the 700,000 soldiers deployed during the war were exposed to DU, when they were fired upon or went into destroyed tanks to rescue others. But scientists and military whistle-blowers who have studied the campaign say the number of soldiers exposed to DU dust and debris is closer to 300,000. Soon after the fighting stopped, soldiers who worked on supply lines at the rear were loaded on buses and taken to the battlefields so they could be photographed with their comrades on burned-out Iraqi tanks. No one warned them to avoid the sticky black soot coating the vehicles, which was radioactive.

Within months of the war's end, thousands of Gulf War veterans began suffering from odd, nameless maladies, including hair loss, bleeding gums, memory loss, joint pain, incontinence. and disabling fatigue. In 1992, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) asked the General Accounting Office, an independent research arm of Congress, to study American tanks that had been hit by DU rounds during the war. GAO investigators learned that most soldiers had never been informed by their superiors about the hazards of DU. The GAO's findings were summarized in the title of its report issued a year later: "Army Not Adequately Prepared to Deal with Depleted Uranium Contamination".

Military and civilian doctors agree that the host of ailments now known as Gulf War Syndrome were probably caused by a multitude of physical insults: vaccinations, pesticides, toxic solvents, and oil fires (which deposited a film in the nostrils so thick that soldiers relied on Popsicle sticks to remove it). But many of the diseases -- including increased rates of lymphoma -- are consistent with either radiation sickness or the toxicological effects of exposure to depleted uranium.

It will take years, if not decades, to determine how much of a role DU played in the illnesses, but the sheer magnitude of the problem could make the struggle over Agent Orange, the cancer-inducing chemical used to defoliate jungles during the Vietnam War, look like an encounter with Dr. Phil. More than 150,000 veterans of the first Gulf War are currently on medical disability, and another 50,000 have applied for benefits -- nearly one-third of the entire fighting force. By comparison, nine percent of veterans from World War II and the Vietnam War applied for similar compensation.

"About two weeks after I was wounded, I was sent back to Germany. There was a lot of shrapnel -- my sleeping bag had eighty-two holes in it. All my gear was filled with holes. I brought it all into the house. I had a son who was three months old at the time. Within twelve hours, I was taking my baby to the hospital for respiratory problems. They kept him there for three days.

"About two weeks after I was wounded, I was sent back to Germany. There was a lot of shrapnel -- my sleeping bag had eighty-two holes in it. All my gear was filled with holes. I brought it all into the house. I had a son who was three months old at the time. Within twelve hours, I was taking my baby to the hospital for respiratory problems. They kept him there for three days."I left Germany in December of 1991. I started having really bad abdominal cramps. I couldn't hold my food down. I was discharged, so I had no health insurance. Then, my wife miscarried, and no one knew why.

"In March, my dad calls me and says, 'Hey, did you know you were hit with depleted uranium?' I had given my dad a bunch of the shrapnel. I could still squeeze pieces out of my body. I had another piece up in my head. My dad was an industrial-hygiene technician for the Los Alamos labs. So he decided to put a Geiger counter to the shrapnel. It was radioactive -- the highest possible reading you can get. To this day, it's still in my system, and it's not losing any of its radioactivity."

THE PENTAGON NEXT USED DU weapons in the Balkans in 1994 and 1995. Just as there is a disease called Gulf War Syndrome in this country, there is a corollary in Europe: Balkans Syndrome. Four years later, NATO pilots fired DU ammo at Serbian tanks in Kosovo, leaving thirteen tons of DU on the ground, according to the Pentagon. When the United Nations recently measured radiation at eleven sites in Kosovo where NATO fired DU rounds, eight were found to still be contaminated.

Europeans are more acquainted with the DU controversy than Americans, in large part because a handful of Italian soldiers, most of whom were sent to Yugoslavia as peacekeepers when the Balkans conflict ended, developed leukemia. When seven of the Italians died, and the deaths of at least nine other Balkan veterans were linked in news reports to DU exposure, anti-DU fervor rapidly swept across Europe.

In Geneva, the Human Rights Tribunal declared DU projectiles weapons of mass destruction. The United Nations has made its position on depleted uranium abundantly clear: Use of such weapons is illegal, because they continue to act after the war ends, they unduly damage the environment, and they are inhumane. Next month, the first international conference on eliminating such weapons will convene in Germany; a country that outlaws the use of DU munitions.

"Depleted uranium weapons are radioactive weapons, even if they are not by definition nuclear weapons," says Victor Sidel, co-president of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War and an expert in weapons of mass destruction. "And because they are radioactive, their use is contrary to international law."

But the Bush administration remains un-swayed by international opinion. The U.S. used DU weapons in Afghanistan, though the Pentagon will not say how much or where. In Iraq, the A-10 "Warthog", the Apache helicopter, the MI Abrams tank, and the Bradley fighting vehicle were all equipped with DU. The Pentagon won't reveal how much depleted uranium it deployed in Iraq. "I can't reasonably guess," says the Army's Naughton. "Even if I gave you a guess, it would be classified." Nor will he say how much DU is left over from the first Gulf War. "It's not as if there's a massive pile of DU where we could say, 'Hah, here it is,' and clean it up."

But the Bush administration remains un-swayed by international opinion. The U.S. used DU weapons in Afghanistan, though the Pentagon will not say how much or where. In Iraq, the A-10 "Warthog", the Apache helicopter, the MI Abrams tank, and the Bradley fighting vehicle were all equipped with DU. The Pentagon won't reveal how much depleted uranium it deployed in Iraq. "I can't reasonably guess," says the Army's Naughton. "Even if I gave you a guess, it would be classified." Nor will he say how much DU is left over from the first Gulf War. "It's not as if there's a massive pile of DU where we could say, 'Hah, here it is,' and clean it up."Dan Fahey, a former Navy officer deployed in the Gulf in 1991, has reviewed the latest military assessments. He estimates that as many as 176 tons of DU were used in the second war on Iraq, roughly one-third to one-half the amount used in the first. In May, the Christian Science Monitor's Scott Peterson, who was touring battle sites with a Geiger counter, reported that Baghdad and other cities were littered with DU ordnance, all of which was producing extremely high levels of radiation.

But the Bush administration flatly rejects Iraqi reports that lingering radiation from the first Gulf War is causing lymphoma and leukemia among civilians. A month before DU-plated American tanks began their steady crawl into Baghdad, the White House issued a report called "Apparatus of Lies: Saddam's Disinformation and Propaganda". The report implies that Iraq's "baby funerals", blocks-long processions of marchers carrying infants' coffins, were staged by Saddam to ward off DU attacks. "Uranium is a name that has frightening associations in the mind of the average person, which makes the lie relatively easy to sell," the report states.

Naughton is equally dismissive. "If you go to a cancer ward, you should expect to find cancer patients," he says. "If you go to a casino, you should expect to find gambling going on. The question that needs to be asked is whether the occurrence of cancer in Iraq is higher than places where there's been no DU. Aside from the fact that we're bombing the crap out of Iraq, and did so twelve years ago, what is the general state of the environment over there? I would look in the water. I'm pretty well convinced it's not DU."

Jim McDermott isn't so sure. The imposing, white-haired Democratic congressman from Seattle, who is also a doctor and child psychiatrist, visited hospitals in Iraq in September 2002. "I spent a good deal of time looking at the increase in childhood leukemia, lymphoma, and malformations -- which are felt by the doctors there to be directly related to the residue from the use of depleted uranium," McDermott says. "These are serious malformations -- without eyes, limbs. One obstetrician told me, 'The average Iraqi woman giving birth no longer says, "Is it a boy or a girl?" She asks, 'Is the baby normal?'" McDermott studied the records Iraqi doctors were keeping that show a rise in birth defects after the war. "You can say, 'They made it all up.' That's one explanation," he says. "But if they didn't make it all up, then there is something we made happen when we brought that war there. It would be a tragedy for us to bring democracy to Iraq and leave in our wake a horrendous cloud of nuclear waste."

"It felt like someone was ripping out my insides. I was going to the hospital in Albuquerque. They didn't know what was causing it. Back then, no one was saying, 'Gulf War Syndrome.' I didn't have a place to live. I was sick. I had just been put out of the military.

"It felt like someone was ripping out my insides. I was going to the hospital in Albuquerque. They didn't know what was causing it. Back then, no one was saying, 'Gulf War Syndrome.' I didn't have a place to live. I was sick. I had just been put out of the military."Since I've been back, I've had joint pain, abdominal pain, headaches, minor respiratory problems -- shortness of breath, my lungs make gurgling sounds. I don't run. I walk everywhere. Last time a doctor asked me to blow into a hose to check my lung power, I puked. I take methadone every day for the joint pain. My foot goes numb on me. I get shooting pains in my legs. In 1993, 1 went from 220 pounds to 160 in three months for no reason. The VA just said, 'If you could figure out how you did it, you would be a rich man.'

"My left arm started hurting several years after the war. They did a biopsy at the VA hospital in Baltimore, and said, 'It's not cancer, but we're going to take it out of you anyway.' So in 1998, 1 had a tumor taken out of a bone in my arm. When I went in to have it removed, I asked them to send it to a hospital in Canada. But they got rid of it! They said they sent it out to one of their military hospitals to be examined. I have no idea what they found, but lately my right arm is feeling like my left arm.

"I'm in touch with a couple of my crew -- my gunner and my loader. My gunner's still in active duty. He's had health problems, but he didn't want to say anything or he would be kicked out of the military. The loader -- the same.

"I'm only thirty-six right now, and I'll be lucky if I make it another two years before I can't work."

THE BUSH ADMINISTRATION HAS BEEN equally adamant in denying a link between depleted uranium and the host of illnesses suffered by American troops. So far, the Veterans Administration has agreed to study only ninety soldiers who were exposed to depleted uranium. "There has been no cancer of bone or lungs," Michael Kilpatrick, the military's top spokesman on Gulf War Syndrome, told journalists last March. He added that the vets, twenty of whom carry DU fragments in their bodies, have suffered "no medical consequences of that depleted uranium exposure."

Kilpatrick failed to mention that one of the vets being studied had been diagnosed with lymphoma, and that Jerry Wheat, who continues to report for testing twice a year, had a bone tumor. He also neglected to mention that every vet in the study continued to excrete depleted uranium in their urine nine years after their exposure -- evidence that DU is present in their organs and tissues.

The few independent studies that have been done on Gulf War veterans also suggest a link between depleted uranium and cancer. Han Kang, an environmental epidemiologist at the Department of Veterans Affairs who examined death certificates of Gulf-War-era vets, discovered a thirty percent increase in lymphoma. And Richard Clapp, an environmental epidemiologist at Boston University, used state medical records to track cases of cancer among 30,000 vets in Massachusetts. The statistical likelihood of finding even a single case of lymphoma among such a small sample is zero. So far, Clapp has found four.

Clapp warns it is too soon to draw conclusions from his research, noting that it usually takes at least ten years for those exposed to radiation to develop lymphoma. "That's especially true of other kinds of tumors such as lung cancer and solid cancers," he says. "So we have to keep looking at this."

The federal government, however, has supported almost no independent research into the effects of DU exposure. "The government depends on its own agencies for its information," says Rosalie Bertell, an expert in the relationship between low-level radiation and cancer who has been turned down for federal grants to study Gulf War vets. "Unless you say what the Pentagon says they won't pay any attention to you."

Bertell and other scientists are looking into how the fireballs created by DU explosions spew vast clouds of radioactive dust into the atmosphere. The military insists that such "oxides" fall to the ground within fifty meters of a target. But Asaf Durakovic, a retired Army colonel and former chief of nuclear medicine at the VA hospital in Wilmington, Delaware, calls the assertion "a mind-boggling admission of ignorance. The particles remain permanently suspended in the atmosphere. And dust containing depleted uranium has been detected several dozen miles from the point of impact." Twenty years ago, he notes, a physicist in Schenectady, New York, detected depleted uranium in his workplace, thirty-eight miles from a plant manufacturing DU weapons.

Chris Busby, a British specialist in low-level radiation, conducted his own field assessments in Iraq before the second Gulf War and measured radiation more than 100 times normal near target sites. He concluded that oxide particles are blown far afield by the wind. Such super-fine particles cannot be dislodged from the lungs by coughing; some will make their way into internal organs and bone, where they can irradiate nearby cells and eventually cause genetic mutations that lead to cancer.

Indeed, there is now concern that the latest fighting produced another Gulf War Syndrome. Two service members are dead, and at least sixteen others have been placed on life support as the result of a mysterious aliment that is afflicting U.S. soldiers in Iraq. The Army is investigating, but so far is unable to explain the illness.

WHEN THE FIRST GULF WAR ended in 1991, the military needed to bring home fifteen damaged tanks and nine troop transports contaminated with depleted uranium. Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf asked Maj. Doug Rokke to head the effort to clean them up. The top brass knew the mission was dangerous. Rokke remembers those at the command level telling him, "We've got our Agent Orange of the Nineties."

WHEN THE FIRST GULF WAR ended in 1991, the military needed to bring home fifteen damaged tanks and nine troop transports contaminated with depleted uranium. Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf asked Maj. Doug Rokke to head the effort to clean them up. The top brass knew the mission was dangerous. Rokke remembers those at the command level telling him, "We've got our Agent Orange of the Nineties."Rokke went to Iraq with several hundred men under his command. "I planned how the decontamination should be undertaken," he says. "Nobody really knew anything about it then. We were wearing what we had available -- gas masks and anti-contamination suits and coveralls. I was scraping up body parts from these tanks with a putty knife. If you listen to the briefings today, they say, 'All you need is a dust mask.'"

When it was all over, Rokke received a citation for meritorious service. That wasn't all he got, however. Today he suffers from cataracts, kidney damage, and a disease called RADS -- a lung-destroying malady caused by inhaling hazardous substances over short periods. Another colleague, an engineer, developed throat cancer nine months after the decontamination project and died. Rokke claims that thirty other men who worked with his team eventually died of cancer. Ask him about his own health today, twelve years later, and he says simply, "I'm trashed."

Ultimately, Rokke and his team shipped the vehicles to a military facility in Barnwell, South Carolina. "It's a giant facility that deals with the recovery of radioactive-contaminated equipment," he says. "There are exceptional scientists there, but it took three years to clean up twenty-four vehicles." Some of the vehicles, he says, were sent back into service, where they joined thousands of others that remain contaminated. Cleaning them up, he says, "is not even feasible."

For the past twelve years, Rokke has tried to educate the military command about the dangers posed by DU. "I recommended medical care for every soldier who had been involved in friendly fire," he says. "They won't do it. They never looked for problems, so they didn't find any. And people wonder why a quarter of the vets are sick? But hey, I'm just a friggin' blue-jean-type moccasin scientist. I'm not a lab guy. I'm the guy who is scraping this stuff up with a putty knife. It's real simple: This stuff is effective, and they're going to use it. If they acknowledge what happened to the vets, they have to acknowledge what happened to the non-combatants. There are sick people all over the Gulf."

THE THREAT POSED BY DU ISN'T limited to Iraqi civilians and U.S. soldiers. The military has been testing depleted uranium at home, even firing missiles into the Pacific. "We've fired DU all over the country," says Naughton, the retired Army spokesman. "If you shoot it into the same area over and over, you create a contamination problem that's just not worth cleaning up. If you have enough DU lying around, someone is going to ask you to clean it up, and you would rather not do that."

Depleted uranium has attracted its share of conspiracy theorists. Some say the military is deploying DU to help rid the United States of nuclear waste; others charge the Pentagon with genocide, claiming that radioactive weapons are being used to deliberately destroy the genetic future of targeted populations in Iraq and elsewhere. But even the most measured activists who take pains to distance themselves from such claims say the military is distorting the truth and putting troops at risk to keep its silver bullet in action. "The Pentagon is lying," says Dan Fahey, the former Navy officer. "This is the precedent that has been established with atomic veterans and with Vietnam veterans. If they're not going to let us know what they know, they should give the benefit of the doubt to the veteran. But they don't want anyone telling them what weapons they can and cannot use."

The military is certainly worried that public opposition could put an end to its favorite weapon. As early as 1991, Lt. Cola M.V. Ziehmn of the Los Alamos labs in New Mexico sent a memo to his bosses at the Pentagon warning that, "DU rounds may become politically unacceptable and thus be deleted from the arsenal." Naughton concedes that the press briefing on depleted uranium held a few days before the attack on Iraq last March was called to blunt criticism. "There have been considerable efforts by a variety of people and institutions to take DU away from the U.S. Army," Naughton says. "We used a little bit in Kosovo and got a really big reaction from our allies. The public-affairs people just wanted to get out there before the shooting started -- before people start complaining there are sick people in Iraq."

Chris Hellman, the military-policy analyst, says the Pentagon is ultimately unconcerned with whether it is turning entire areas of countries into radioactive hot zones. "That's not the military's view of this," he says. "When they wake up in the morning and look at Iraq, number one is to win the war." The only way to put a stop to depleted uranium, he adds, is for Congress to pass a law banning DU ordnance. "It's up to the policy-makers to make this decision for them. It's the policymakers, not the military, who make decisions about morality and 'collateral damage'."

Left to its own devices, the military has made clear that it considers depleted uranium worth any risk it poses. "The military benefits are so much larger compared to any health problems," Naughton says. "We feel we have to use it. It's radioactive -- I wish it wasn't, but I can't change the laws of physics. The issue is, once you've had the hit, once you're involved in the catastrophic failure of the tank, did the crew survive long enough to really care whether it was tungsten or DU that hit them? Anyone who does should count themselves damn lucky. I'm sure every one of them would thank God that they lived forty years to contract lymphoma."

"I don't even know what to say about the Veterans Administration. I put in for disability on my back and they won't give it to me. I spoke with the chief investigator of the study, and I don't know whether she's downplaying it or what. She said, 'DU doesn't hurt you.' That was pretty much what she said in a nutshell. But that study is funded by the government, and I guess if I wanted the job, I would say what the government wants, too.

"At first, being hit with friendly fire really disturbed me. But at that point, I wasn't really aware of any problems with DU. Over the years, I've kind of changed. The friendly fire has become less important to me, and the DU is concerning me more and more.

"I personally think the Pentagon is covering this up. They have a shameful history of hiding these things from the vets. It's not until half of these people are dead or coming down with cancer that they say, 'OK, now we're going to take care of you.' Don't take me as un-American or anything, but there's no way in hell I would want one of my sons out there fighting now."